Top 5 InfluxDB alternatives

Since its initial release in 2013, InfluxDB has held a prominent position in the time-series database ecosystem. As a pioneer in this space, InfluxDB gained widespread adoption across observability, application monitoring, and Internet of Things (IoT) use cases. However, a combination of architectural churn, product fragmentation, and persistent performance limitations at scale has led many teams to actively evaluate alternatives.

Thankfully in 2026, the ecosystem for time-series data is now more robust and diverse, offering users powerful–and often much simpler–options depending on their use case. In this article, we’ll explore five compelling InfluxDB alternatives to consider if your team is starting fresh or looking to migrate off InfluxDB entirely.

InfluxDB, history in brief

To understand why teams are reconsidering InfluxDB, it’s useful to look at how the product has evolved. Over the last decade, time-series workloads have changed dramatically. Data volumes exploded, cardinality increased, and new use cases emerged—particularly in cloud-native infrastructure, industrial IoT, and financial data. In response, the InfluxData team introduced multiple major architectural rewrites in an attempt to keep pace.

These changes included:

- A rewrite of the core engine from Go to Rust

- Multiple query-language pivots—from SQL-like InfluxQL, to Flux, and now SQL

- Fragmented product structure with changes spread across several cloud-specific offerings, including serverless, single-tenant, and multi-tenant variants

Most recently, InfluxDB 3.0 Core (finally) reached general availability in April 2025 after a long incubation period once the cloud-only InfluxDB 3 was released way back in April 2023. This gave users a clearer split between InfluxDB Core (open source) and commercial enterprise offerings that have been in flux (no pun intended) for a while. For a long time, decoding InfluxData team’s product roadmap was a guessing game to figure out what will be cloud-only or open-source.

On the technical front, InfluxDB 3 introduced a SQL-based engine built on Apache Arrow and Parquet, validating many SQL-first design decisions and other industry standards already proven elsewhere in the TSDB ecosystem. Unfortunately, while InfluxDB 3 significantly modernized the execution engine, users still encounter query limits, performance ceilings on large datasets, and architectural constraints once workloads move beyond “metrics-only” scenarios. Lack of focus and huge churn has left InfluxDB vulnerable to the deepening state of the art, falling behind the performance curve.

This has left a lot of the InfluxDB users in a tough position. For those still on the legacy product (either InfluxDB v1.x or v2.x), they must choose to undergo a major technical overhaul to InfluxDB 3 Core or change product models to the cloud-hosted version. Or for many, they are choosing to reassess the database choice altogether given the cost to just stay up to date in the InfluxDB ecosystem.

Prometheus, the observability powerhouse

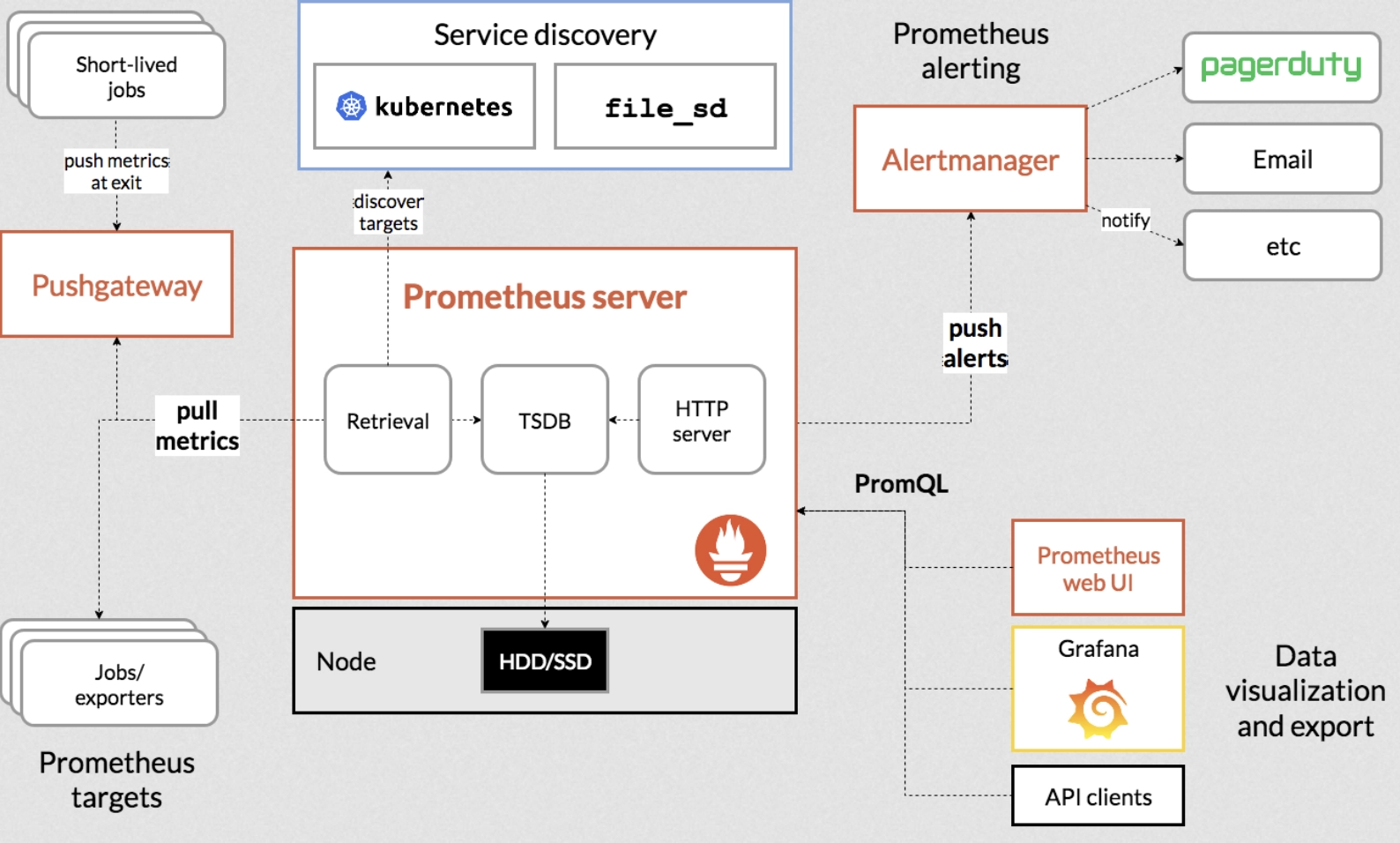

If your main use case is capturing observability data such as server metrics, then Prometheus remains the most widely adopted solution in the market today. Originally developed by SoundCloud, Prometheus was one of the first projects to be accepted to Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) and remains one of the most used and supported CNCF projects along with Kubernetes.

Prometheus is primarily a monitoring software that efficiently collects, stores, and analyzes metric data with native alerting capabilities built-in. It typically scrapes a HTTP endpoint that exposes Prometheus metrics (e.g., counters, gauges, histograms, and summaries) and aggregates them for analysis. Prometheus metric format has since then been absorbed into the OpenMetrics and OpenTelemetry projects to establish a de facto standard for observability data.

Although Prometheus can be used as a standalone product, it is often deployed with other popular open-source observability tools such as Grafana for visualization and PagerDuty for alert notification and incident management. Over the years, Prometheus has built up a rich ecosystem of observability solutions and has solidified itself as the de facto database for observability use cases, especially in cloud-native environments.

While Prometheus is a strong fit for a real-time monitoring or as part of a wider observability stack, it’s important to note that Prometheus is not a true time-series database like others in this article. It contains a time-series database under-the-hood, supported by components specifically designed for observability. With that said, there are trade offs:

-

Prometheus has a specific data model to ingest metrics in a standard format

-

Prometheus needs to be paired with another solution to handle long-term storage like Thanos or Grafana Mimir

-

It uses its own query language PromQL instead of standard SQL

To go a little deeper, as written in the blog Prometheus Is Not a TSDB, author Ivan Velichko explains:

Aiming for results that would be reasonable for a pure TSDB apparently may be way too expensive in a monitoring context. Prometheus, as a metric collection system, is tailored for monitoring purposes from day one. It does provide good collection, storage, and query performance. But it may sacrifice the data precision (scraping metrics every 10-30 seconds), or completeness (tolerating missing scrapes with a 5m long lookback delta), or extrapolate your latency distribution instead of keeping the actual measurements (that's how histogram_quantile() actually works).

So if observability is what you're after, consider Prometheus.

kdb+, the sticky finance classic

kdb+ is a proprietary, high-performance time-series database from KX that’s long been a default choice in capital markets—especially in high-frequency and low-latency environments. Its columnar, in-memory design and the q language make it extremely good at working with tick data and real-time/streaming analytics (joins, aggregations, and vectorized operations) at scale.

That story is starting to broaden. In late 2025, KX introduced KDB-X and released KDB-X Community Edition—-a free edition aimed directly at developers building modern “time-aware” applications for AI-era workloads. The positioning is explicitly lakehouse-friendly and modular, with a simplified install and “developer tools” focus rather than “you need a specialist q team to get started.”

This matters if you’re evaluating InfluxDB alternatives, because it changes the first impression of the KX ecosystem:

- Lower barrier to trial and prototyping: Community Edition gives developers free access to KDB-X to build and experiment without immediately committing to enterprise licensing.

- More “modern stack” interoperability: KDB-X is positioned as a unified engine spanning time-series + real-time workloads and designed to fit modern lakehouse architectures (modular building blocks, “tools developers use,” etc.).

- Not just q-first anymore: KX is explicitly talking about meeting developers where they are, with broader interoperability (e.g., SQL/Python mentioned in KDB-X materials) while maintaining continuity with the kdb+ core.

That said, the classic caveats still apply—especially if you’re coming from InfluxDB and want optionality:

kdb+ (and the broader KX stack) remains proprietary at its core, which can mean higher long-term costs, more contractual coupling, and a steeper, ecosystem-specific learning curve. And while KDB-X aims to reduce friction with more modular architecture and developer-friendly onboarding, many teams will still feel the gravitational pull of q-centric workflows and KX-specific operational patterns once they move beyond a proof of concept.

If your workload is market data, real-time analytics, or latency-sensitive time-series at large scale, the KX ecosystem deserves a serious look—and KDB-X Community Edition makes it easier than before to evaluate. But if your priority is avoiding lock-in and leaning on broadly portable skills and open ecosystems, kdb+/KX may still be a tougher migration target than SQL-first, open-format alternatives.

TimescaleDB and KairosDB, the "built atop" databases

Next we will look at two more general time-series databases: TimescaleDB and KairosDB. While general, both are time-series databases that are built on top of other databases, with TimescaleDB built atop PostgreSQL and KairosDB built atop Apache Cassandra. This brings about interesting advantages and limitations as each of these databases are inevitably tied to the underlying infrastructure and architecture of their hosts.

TimescaleDB & PostgreSQL

Now branded under TigerData, TimescaleDB is an open-source PostgreSQL extension that adds time-series optimizations through hypertables, chunking, and specialized SQL functions.

The primary advantage is ecosystem compatibility. PostgreSQL is the most widely used database in the world, with a massive ecosystem of tooling, drivers, and operational expertise. TimescaleDB allows teams to extend that foundation rather than replace it.

Compared to vanilla PostgreSQL, TimescaleDB offers substantial improvements in time-series performance and storage efficiency. TimescaleDB extends PostgreSQL’s row-based architecture with a hybrid row-columnar storage engine called Hypercore. Recent data is stored in row formats for fast inserts, while older data is converted into columnar format with compression. Large data is automatically partitioned into chunks based on time intervals and space to facilitate efficient data management. With these clever solutions, TimescaleDB is able to outperform PostgreSQL while staying within the ecosystem.

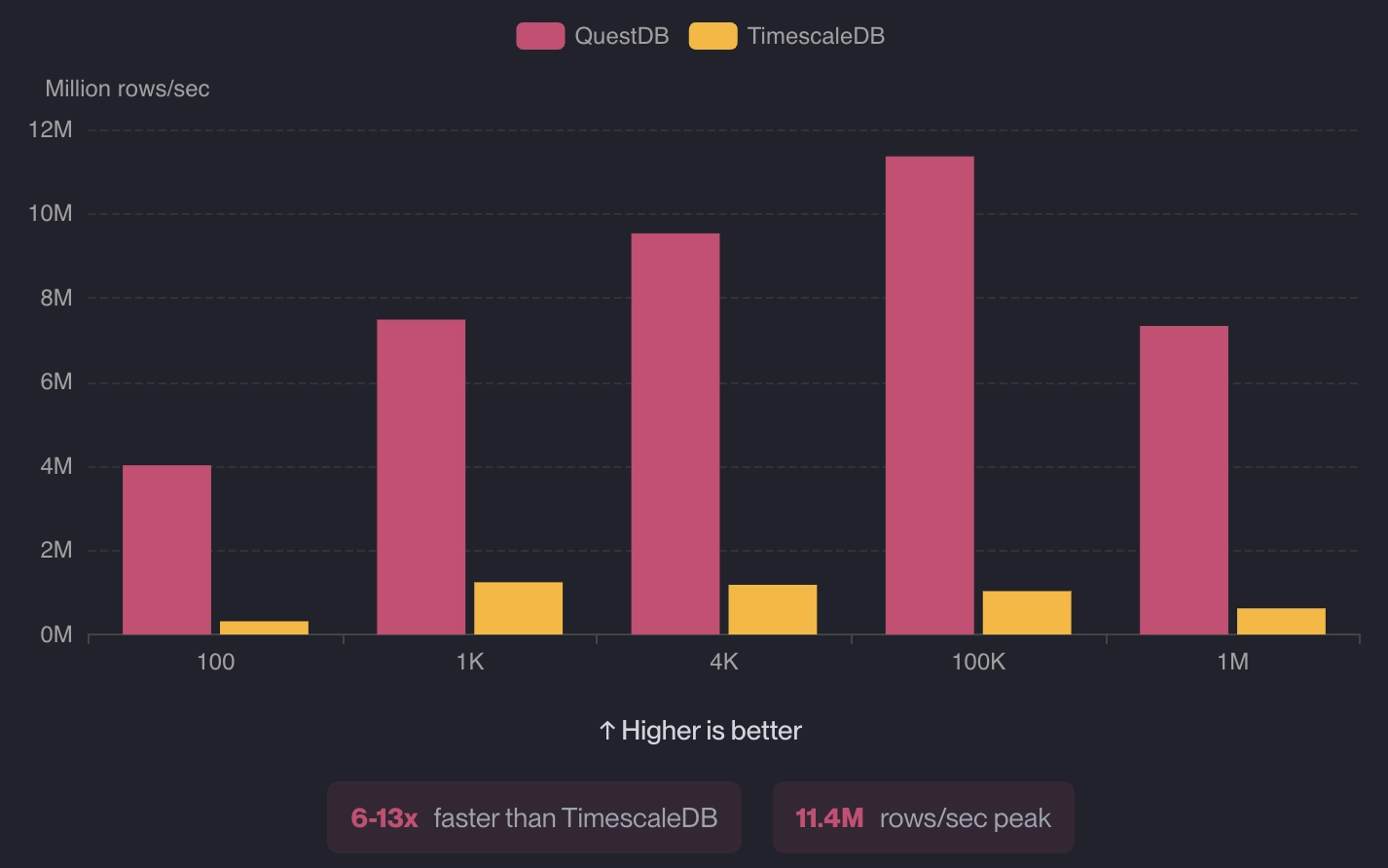

However, as PostgreSQL remains a general-purpose, transactional database, these roots still impose limits at scale. While TimescaleDB shines against vanilla PostgreSQL, compared to modern, pure-TSDBs, ingestion and query performance lags significantly. When large data sets with high cardinality or long-horizon analytics are involved, TimescaleDB requires complex tuning or distributed PostgreSQL setups to compete. For a deeper look at these trade-offs, see the dedicated benchmark comparison.

Lastly, TimescaleDB has expanded into AI and hybrid analytics as part of their rebrand into TigerData. The focus has shifted away from supporting time-series data into integrating tools like pgai and pgvectorscale, which may appeal to teams combining time-series data with AI workloads rather than looking for pure performance.

KairosDB & Apache Cassandra

On the NoSQL side, we have KairosDB, which is built on top of Cassandra. Originally developed at Facebook, Cassandra is a mainstay in distributed computing and big data. The advantages to using KairosDB is largely similar to the rationale given for TimescaleDB. The large community and infrastructure for Cassandra is a huge plus for existing users of Cassandra.

While powerful, Cassandra is notorious for its maintenance and management overhead, especially regarding performance tuning and repair operations. This rolls into KairosDB, and can present a huge challenge for teams who are not so familiar with the operational aspect of running a Cassandra cluster. In practice, KairosDB sees far less active adoption and development today (there were zero feature releases in 2025), making it a less common choice for new deployments unless a team already operates Cassandra at scale.

QuestDB, pure time-series performance

So far, we’ve seen examples of databases specializing in a certain use case, such as Prometheus for monitoring and kdb+ for financial markets. We’ve also looked at databases which leverage existing database ecosystems for compatibility and ease-of-use, namely TimescaleDB with PostgreSQL and KairosDB with Cassandra. Each of them came with a different set of tradeoffs.

Next, we’ll look at a purpose-built, time-series database designed from the ground up for high ingestion rates, low-latency queries, and analytical workloads without the proprietary lock-in. QuestDB is a highly-performant, time-series database designed to handle the highest data volumes while leveraging open protocols and familiar SQL.

Let’s break down each of its characteristics.

Fast ingestion and query speed

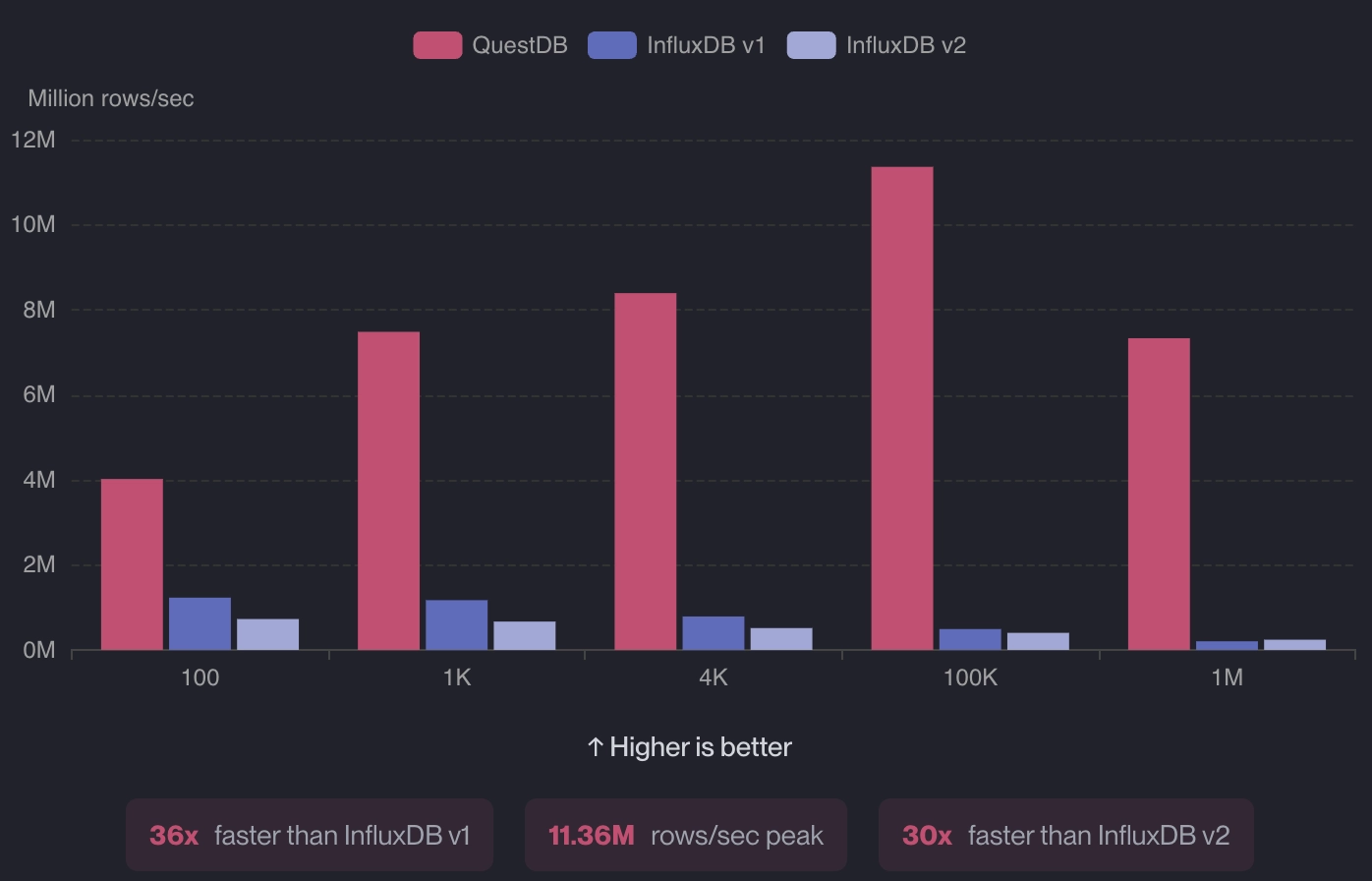

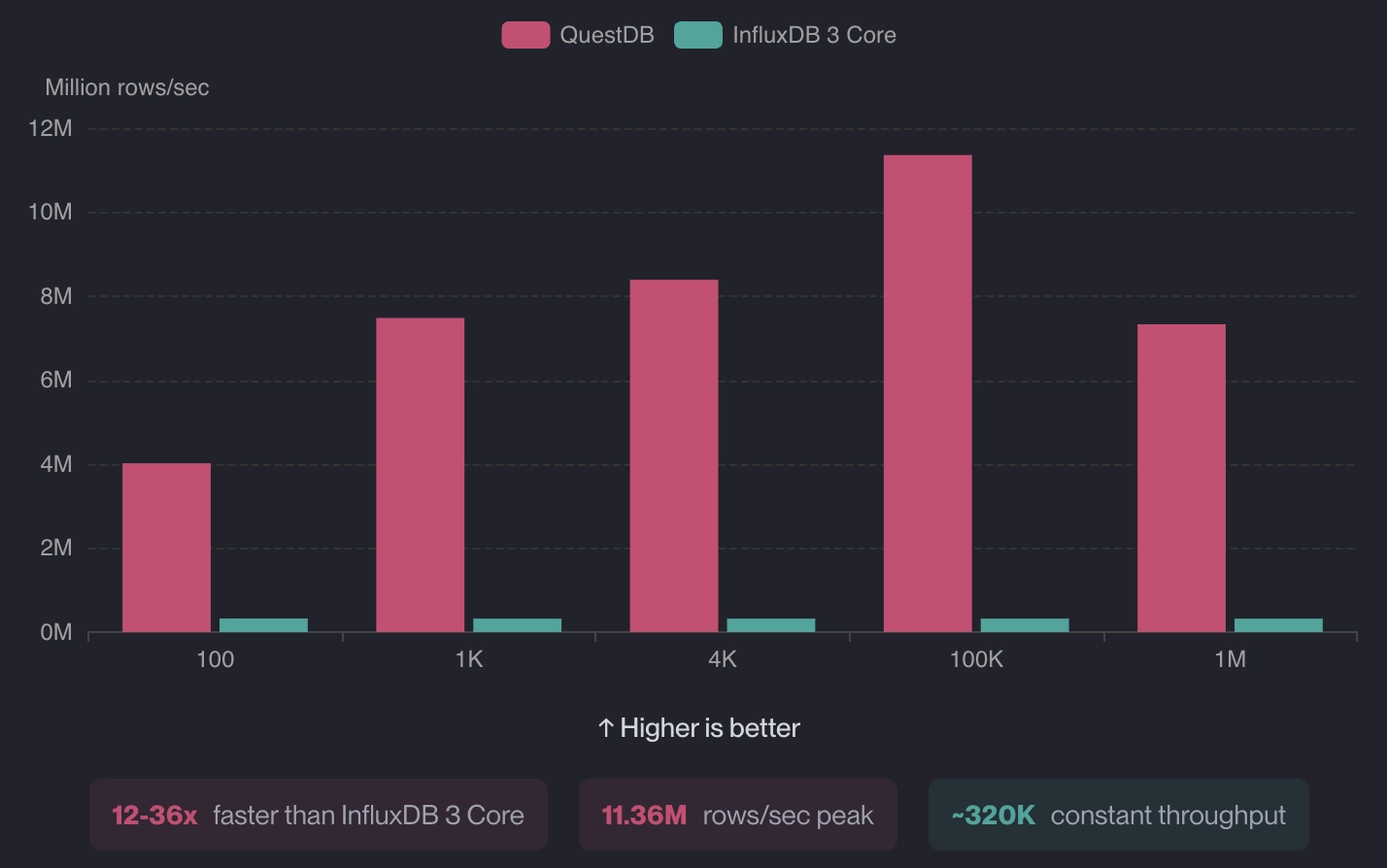

While benchmark results can be skewed based on dataset and infrastructure setup, they still provide a useful measure for relative performance. Check out the benchmark numbers against all three variants of InfluxDB:

QuestDB is 3.3x to 36x faster than InfluxDB v1 and v2 in terms of ingestion. For single-groupby queries, QuestDB was up to 4.2x faster, and delivered whopping 21-130x faster on double-groupby queries.

The story is much the same against InfluxDB 3 Core: QuestDB was 12-36x faster in terms of ingestion and 43-418x faster for single-groupby queries and 28-35x on double-groupby queries.

When running similar comparisons with TimescaleDB, QuestDB was 6-13x faster in terms of ingestion and 16-20x faster on complex queries:

Flexible ingestion

Another nice feature of QuestDB is its flexible ingestion protocol support. Users can leverage InfluxDB Line Protocol, PostgreSQL wire, or REST API to load the data in whatever way that works best. This makes migration from InfluxDB or PostgreSQL straightforward, often without rewriting ingestion code.

SQL-first design

Unlike older versions of InfluxDB and kdb+ that enforce its own set of domain-specific language (i.e., InfluxQL, Flux, q), QuestDB has been SQL-native since day one. There is no secondary DSL, no translation layer, and no semantic mismatch between ingestion and querying–unlike systems that adopted SQL later in their lifecycle. This reduces the learning curve to get started significantly.

Financial-grade data modeling

While QuestDB can be used for any time-series data, it has increasingly added support for financial workloads such as:

- Nanosecond timestamps

- Native decimal support

- N-dimensional arrays for L2+ order books and sensor girds

- Strong high-cardinality performance

These capabilities make it well-suited for tick data, L2/L3 order books, spreads, and depth analytics, using the familiar SQL semantics.

Clear roadmap with open-source

Finally, QuestDB has integrated popular open-source formats such as utilizing Apache Parquet to store data. This popular open-source, column-oriented data file allows users to decouple storage and compute, so that they can load and unload data in native Parquet format on S3 directly if needed for better performance or ease of integration.

QuestDB in a nutshell

Many of QuestDB's largest customers are big players in finance, from hedge funds and traditional exchanges, to emerging crypto exchanges. These organizations found an alternative solution to InfluxDB's performance bottlenecks, avoided the vendor lock-in from kdb+, and liked the long-term, public roadmap better than OLAP or other analytics and time-series competitors.

Wrapping Up

In this article, we’ve looked at five alternatives to InfluxDB to consider, starting from Prometheus to QuestDB. Even though InfluxDB remains a major player, especially with the GA release of InfluxDB 3 Core signaling a meaningful technical and product reset, the time-series ecosystem has matured compared to 10 years ago. Teams now have clear, specialized alternatives to migrate or onboard time-series data depending on their needs.

Prometheus continues to dominate observability. Others like kdb+ have an established presence in the financial markets. We have also seen database technologies like TimescaleDB and KairosDB extend the capabilities of the underlying database. And last but not least, we have purpose-built, time-series databases designed to handle the needs of modern, time-series use cases.

If you’re planning a new project or reassessing an existing InfluxDB deployment, 2026 is a good time as ever to evaluate what the broader ecosystem has to offer.